Дипломные и курсовые работы являются важной частью образовательного процесса в высших и средних специальных

К чему снится ссора с покойником К чему снится Ругаться с Покойником? Сонник ругаться

К чему снится замороженная рыба: разные варианты и сюжеты. Толкование для девушки, замужней женщины

Сонник выгнать Кота, к чему снится выгнать Кота во сне видеть узнайте что

Если во сне кошка кусает или царапает человека, то наяву у него возникнут трудности

Как правильно интерпретировать сновидение о маленьких либо больших кошках 🐈 и серых, белых или

К чему снится вареная рыба мужчине, женщине, ребенку. Интерпретация сновидения в зависимости от ее

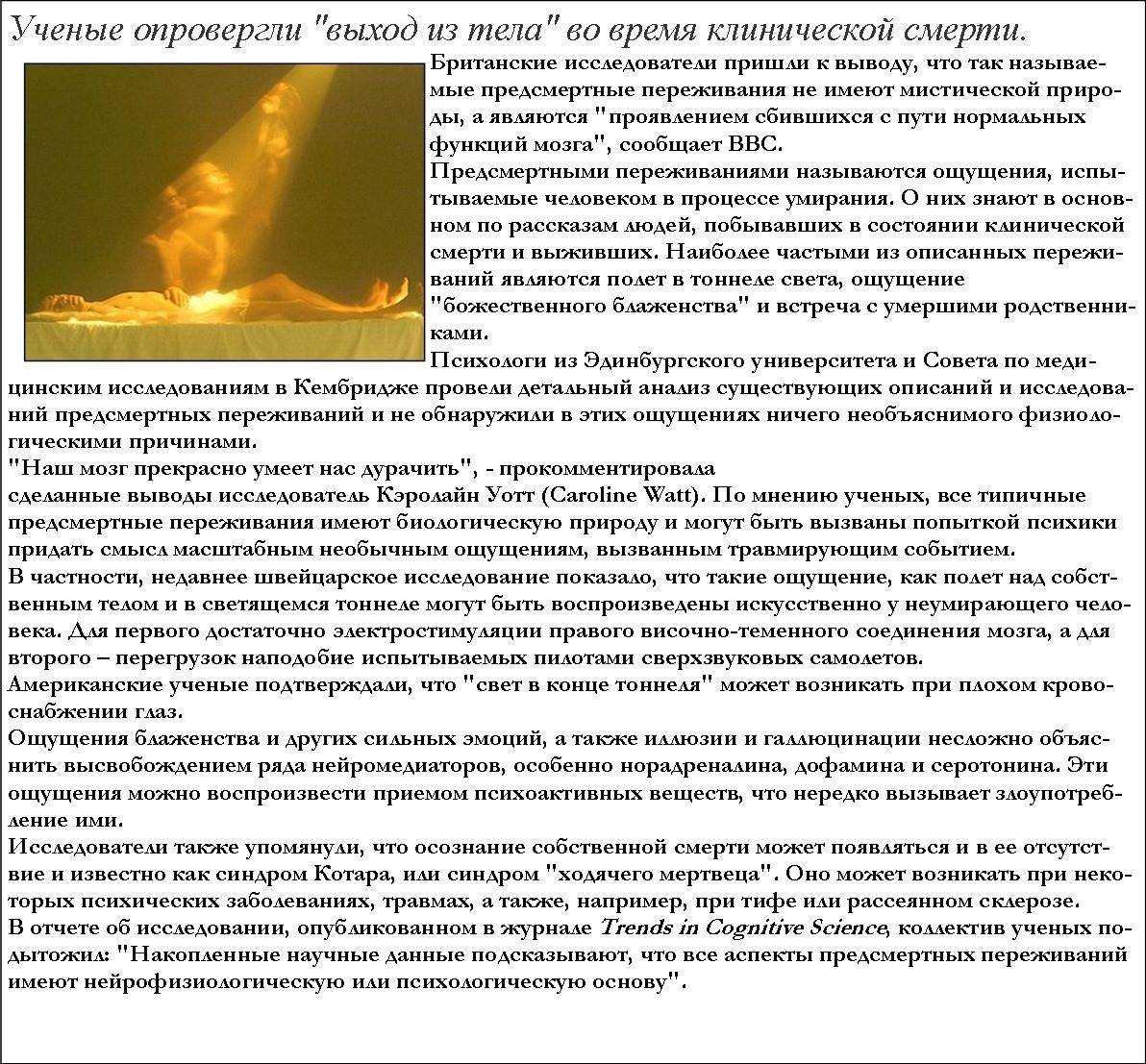

Что происходит с человеком в загробной жизни? Знаки того, что умерший человек хочет с

Увидеть во сне покойника: к чему снятся умершие родители Большинство людей сильно пугаются, когда

Укусила рыба во сне сонник К чему снится Рыба Укусила? Сонник рыба укусила На

💤 Разделывание рыбы во сне: расшифровка снотолкователей для тухлой, свежей и соленой тушки. Значение

. Сновидения, где появляются мертвые люди, олицетворяют внутренние переживания. Второй вариант — сильные, но

К чему снится рыба с червями: общее значение символа, толкование в зависимости от внешнего

Символические сны о смерти людей и животных вряд ли предсказывают такое событие в настоящей

Во сне танцевать с покойником Во сне случилось танцевать с покойником? В текущий момент

Что означает, если снится кушать рыбу? Толкование сна в зависимости от того, кому снится

Когда человеку снится мертвая рыба, он заранее готовится к худшему. В статье мы расскажем,

К чему снится рыба в воде Каждая женщина уверена: если приснилась рыба, плавающая в

Обратитесь к соннику, если во сне увидели, как едите соленую рыбу. В зависимости от

К чему снится собирать яблоки? Что значит во сне собирать яблоки по соннику Миллера,

Сонник Укусила Собака во сне 🐕 К чему снится, что своя собака кусает за

Что означает приснившаяся во сне 🌓 рыжая кошка 🐱? Как трактовать сон, если кошка

Что значит пьяный покойник во сне и к чему снится буйный мертвец, что значит,

К чему снится рыба: 7 основных значений + 5 описаний рыбешек + 7 толкований

Увидеть во сне президента к переоценке жизненных ценностей и не только.

Трактовка снов о покойниках по сонникам Миллера, Фрейда, Ванги. Сны, в которых покойник оживает

Брат что означает во сне? Толкования сонников объяснят, к чему снится Брат женщине или